"It is helpful to understand a little music history in order to better understand the various styles that emerged. In a nutshell, it goes like this: In the West, the music was modal until the late 17th century, at which time the music became tonal (based on chord progressions aimed at culminating in a cadence to the tonic chord). The tonal system prevailed until the Twentieth century, when much of the music tended towards atonalism (no primary key). In atonalism, chords are arranged in successions that have no functionality in a tonal sense, but are used for their color and interest alone. Jazz, however, is basically still rooted in the harmonic practices of the classical and romantic periods (18th and 19th century harmony).

The Berklee system of applying chord scales and modes to chord progressions makes it necessary to theorize in order to arrive at which of these (arbitrary at best) scales are to be applied. In this way, Greek modal names are applied to a tonal chord system that is in no way modal. Indeed, the European composers, whom jazz musicians emulate, rarely employed modes in tonal music: they used non-harmonic tones to propel their lines forward.

This is, I hope, an interesting tidbit of history: A few years ago, while writing my doctoral dissertation, I interviewed Jerry Coker, who was one of the very first to hold a full-time positon as Jazz Professor in a college or university. He admitted to me that he used this modal system--with its Greek names--to impress the classical administrators that dominated the music department—so that they might take jazz education seriously. (They have been in the colleges for well over 100 years, while jazz education was only begrudgedly admitted fewer than 50 years ago.)

Coker explained that had he taught a more direct, common sense traditional approach to this extemporaneous art form, it would have gone right over their heads. They don't like us. The only reason jazz exists in higher education is because of enrollment: Students demand jazz courses.

My method is based on reducing the melody to its essence, and learning the guide tone line and the root progression. I then systematically apply non-harmonic tones. Added to this is a systematic development of the song's rhythms. I find that this approach gets my students and me to the heart of the subject matter--with no unnecessary terms and theories.

A voicing is a voicing; a chord is a chord; a progression is a progression. In tonal music there obviously are only so many ways to make a progression, and the musical elements adhere to general concepts. But these jazz theory books imply that Major seventh b5 (#11) chords, or a Dominant seventh +9 chord, for two examples, are jazz chords. They are not.

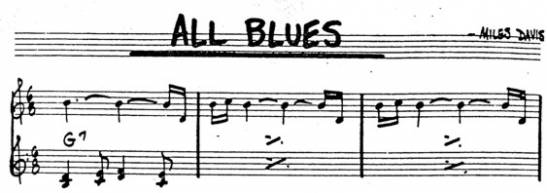

To learn what Miles Davis thought of his music from his modal period (circa 1958-63), the best source is Davis' autobiography, Miles: The Autobiography, in which he states that he was prompted into this style of improvising on fewer chords by Gil Evans' arrangements of George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess. He also states that George Russell recommended pianist Bill Evans (no relation) to Davis around the same time period (1958) for his LP Kind of Blue on the strength of Evans' knowledge of the music of French Impressionist composers Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel. Davis subsequently became infatuated with Revel’s Concerto for the Left Hand, and spent roughly the next 13 years incorporating the latter composer's devices from that particular piece into a distinctive Davis style of what some historians (Winthrop Sargeant, for example) termed Impressionist Jazz: unresolved melodic tensions, quartal harmony, non-functional chord successions (as opposed to progressions), extended pedal points, bi-tonality, and other salient early Twentieth century characteristics.

Having said all of this, however, I must point out that jazz is not modal, including Davis' music of the period in question. Jazz scholar Barry Kernfeld, for example, calls this music Davis' Vamp Style, explaining that this style does not fulfill the musical characteristics which scholars attribute to modal music. Check out the New Groves Dictionary of Music and the New Groves Dictionary of Jazz. In brief, modality is a medieval style based on melody--not chords, unlike Mozart's music, whose melodies are guided by and outline chord progressions which move forward through the circle of fifths towards cadences in tonal keys. True modal music is a melodic rather than a harmonic concept. Even when harmony is introduced to modality, it does not guide its behavior. Moreover, the mere absence of chord progressions--or the presence of pedal points--does not constitute modality.

Since Davis' music was beautiful by most standards, it is beside the point that he misunderstood the term modal. While it has no impact upon the success of his musical statements that he thought of it as such, it nonetheless can be asserted that regardless of the fact that he thought of his music as modal, it doesn't make it so.

This misunderstanding of modality has had a profound effect on jazz improvisation pedagogy. The prevailing approach in modern times is to arbitrarily assign modes to each chord in a tonal progression that was designed to accompany a tonal melody. The larger problem with this approach, however, is that it fails to address the primary stuff of the composition on which one should improvise: melody, guide tone lines, root progression, and melodic rhythms. Moreover, to assign three different Greek mode names to a tonal ii7 V7 IMA7 (D Dorian, G Mixolydian, C Ionian) cadence, for example, is tedious and misleading. That progression is in the key of C Major, and if you combine the three modes, you come up with the obvious: a C Major scale; and in this context it is also less restricting to think globally through the key, rather than locally from chord to chord."

--Ed Byrne

Furtherology: Functional Jazz Guitar | Linear Jazz Improvisation: The Method

Thanks Ed. The chord scale theory and the modal theory is really misleading jazz improvisation students or musicians. I was always suspicious of these approaches to learning to improvise because in my earlier years as a would be saxophonist I met a local mature jazz saxophonist who told me he never used chord scale and mode theories, he just improvised on the dictates of the melody or when he played using a score he would reduce all chords to only major scales or minor scales. This is because some jazz tunes are so fast that you cannot think and play on all those chords using modes. I therefore agree with you fully that one must think globally through the key rather than locally from chord to chord in order to learn to improvise.

ReplyDelete